Introduction

Nervousness is a standard human expertise characterised by quite a lot of signs, together with worrisome ideas, physiologic arousal, and strategic avoidance behaviors (Barlow, 2002). It usually serves an adaptive response to menace by motivating organisms to extend their vigilance and thus reply extra successfully to threats (Marks and Nesse, 1994; Barlow, 2002). Extreme and chronic nervousness, nonetheless, represents some of the prevalent psychological well being issues in the USA (Kessler et al., 2005, 2012; Kroenke et al., 2007) and elsewhere (e.g., Collins et al., 2011 for a assessment). Analysis from numerous literatures signifies that cognitive deficits symbolize a core side of the pathological nervousness that’s related to impairments in private functioning (American Psychiatric Affiliation, 2000; Eysenck et al., 2007; Beilock, 2008; Sylvester et al., 2012). Higher understanding the associations between nervousness and cognitive deficits is due to this fact of nice significance for serving to to handle issues stemming from pathological nervousness.

One particularly lively space of neuroscience analysis geared toward tackling this subject has centered on how nervousness is said to error monitoring. Error monitoring issues the signaling and detection of errors with the intention to optimize habits throughout a spread of duties and conditions, and this monitoring operate is due to this fact a elementary part of behavioral regulation. A rising physique of analysis signifies that nervousness is related to enhanced amplitude of the error-related negativity (ERN) of the human event-related mind potential (ERP), suggesting that nervousness is related to exaggerated error monitoring (Olvet and Hajcak, 2008).

Nervousness just isn’t a monolithic assemble, nonetheless. Researchers and laypersons alike use the time period “nervousness” to confer with many alternative states and traits comparable to “stress,” “concern,” “fear,” amongst others (cf. Barlow, 2002). This confusion contributes to difficulties with describing the nature of the connection nervousness has with error monitoring, and the ERN, extra particularly. Nonetheless, many agree that there’s a helpful distinction between anxious apprehension on the one hand and anxious arousal on the opposite (Nitschke et al., 2001; Barlow, 2002). Anxious apprehension is outlined by fear and verbal rumination elicited by ambiguous future threats whereas anxious arousal is outlined by somatic stress and physiological hyperarousal elicited by clear and current threats. We and others have just lately urged that the ERN is extra carefully related to anxious apprehension than anxious arousal (Moser et al., 2012; Vaidyanathan et al., 2012; Weinberg et al., 2012b).

The aim of the present assessment is to increase on this argument in two necessary methods: (1) by conducting the primary large-scale take a look at of this speculation utilizing meta-analysis, and (2) by offering an in depth conceptual framework that can be utilized to generate mechanistic hypotheses and information future research. Concerning the latter, we leverage 4 key findings about nervousness and cognitive management: (1) anxious apprehension/fear is considerably concerned in cognitive abnormalities in nervousness; (2) anxious efficiency is characterised by processing inefficiency; (3) enhanced ERN in nervousness is noticed with out corresponding deficits in job efficiency; and (4) people with persistent nervousness exhibit enhanced transient “reactive” management however decreased preparatory “proactive” management. We used these findings to develop a brand new compensatory error monitoring account of enhanced ERN in nervousness. Particularly, we recommend that the improved ERN noticed in nervousness outcomes from the interaction of a lower in processes supporting lively objective upkeep, due to the distracting results of fear, and a compensatory improve in processes devoted to transient reactivation of job objectives on an as-needed foundation when salient occasions (i.e., errors) happen. The general format of this integrative assessment follows that of others within the literature by incorporating each empirical and theoretical issues all through the narrative (e.g., Holroyd and Coles, 2002; Shackman et al., 2011; Yeung et al., 2004).

The Error-Associated Negativity (ERN)

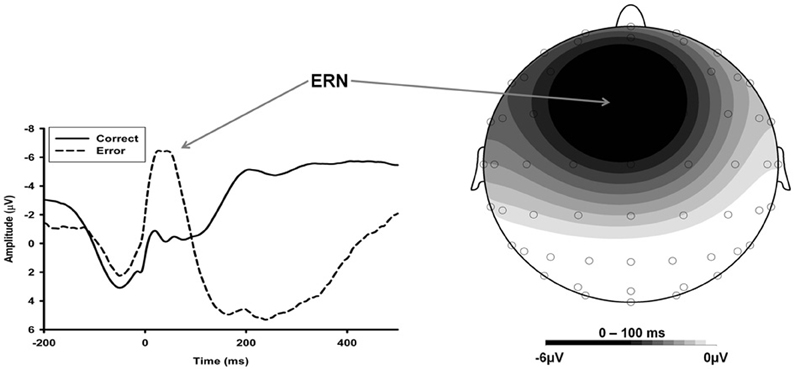

The ERN is an ERP part that reaches maximal amplitude over frontocentral recording websites inside 100 ms after response errors in easy response time duties (See Determine 1; Falkenstein et al., 1991; Gehring et al., 1993; see Gehring et al., 2012 for a assessment). Converging proof suggests the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is concerned within the technology of the ERN. Extra particularly, the dorsal portion of the ACC (dACC) or midcingulate cortex (MCC; Shackman et al., 2011) seems notably necessary to the technology of the ERN (Gehring et al., 2012). The dACC/MCC has neuronal projections extending to motor cortex, lateral prefrontal cortex, parietal cortex, basal ganglia, and emotional facilities such because the amygdala, suggesting that it serves as a “central hub” by which cognitive and emotional data is built-in and utilized to adaptively alter habits (Shackman et al., 2011). It’s important, nonetheless, to differentiate between the ERN and dACC/MCC exercise, because the ERN is a scalp-recorded potential that has a number of attainable sources in different areas of cortex, together with lateral prefrontal, orbitofrontal, and motor cortices (Gehring et al., 2012).

Determine 1. ERN Waveform and Voltage Map. Neural exercise recorded within the post-response interval throughout a flanker job. Response-locked waveform is offered on the left. Dashed line: the ERN is proven because the adverse deflection peaking at roughly 50 ms; the ERN is adopted by a broad, constructive deflection—the error-positivity. Strong line: the CRN is the correct-response counterpart to the ERN. It exhibits the same time course and scalp distribution. A voltage map depicting the scalp distribution of the ERN is offered on the correct. It exhibits that the ERN is primarily a fronto-centrally maximal negativity.

The confluence of cognitive and emotional processing inside the dACC/MCC has contributed to disagreements amongst researchers relating to the practical significance of the ERN. So far, nonetheless, the 2 dominant fashions of the operate significance of the ERN are the battle monitoring (Yeung et al., 2004) and reinforcement studying (Holroyd and Coles, 2002) theories. The battle monitoring concept suggests the ERN displays detection by dACC/MCC of the co-activation of mutually unique response tendencies; the misguided response and the next error-correcting response activated instantly after error onset (Yeung and Cohen, 2006). The reinforcement studying concept suggests the ERN displays the impression on dACC/MCC of a phasic dip in midbrain dopamine launch each time outcomes are worse than anticipated. This mechanism in the end trains the dACC/MCC to maximise efficiency on the duty at hand (Holroyd and Coles, 2002). These theories have each garnered assist within the literature, and extra inclusive “second technology” fashions have been proposed to include each battle monitoring and reinforcement studying facets (Alexander and Brown, 2011; Holroyd and Yeung, 2012).

The ERN and Nervousness

Quite a few research have famous that particular person variations in nervousness are related to elevated ERN amplitude (for critiques, see Olvet and Hajcak, 2008; Simons, 2010; Vaidyanathan et al., 2012; Weinberg et al., 2012b). Essentially the most sturdy proof emerges from analysis on signs and categorical diagnoses of generalized nervousness dysfunction (GAD; Hajcak et al., 2003; Weinberg et al., 2010, 2012a) and obsessive-compulsive dysfunction (OCD; see Mathews et al., 2012 for a assessment). As a result of GAD and OCD are largely characterised by fear and verbal rumination (American Psychiatric Affiliation, 2000; Barlow, 2002), we urged that this work is in step with our thesis that the ERN is most carefully related to anxious apprehension. Certainly, we immediately confirmed that the ERN was extra strongly associated to a measure of anxious apprehension than a measure of anxious arousal in a pattern of feminine undergraduates (Moser et al., 2012). Hajcak et al. (2003) demonstrated the same impact such that the ERN was enhanced in school college students excessive in anxious apprehension however not in college students extremely phobic of spiders. Different latest descriptive critiques of the literature have come to the same conclusion that the ERN is aligned most persistently with anxious apprehension (Vaidyanathan et al., 2012; Weinberg et al., 2012b).

Goals of the Present Meta-Evaluation

Regardless of proof pointing to a selected affiliation between anxious apprehension and enhanced ERN, only a few empirical demonstrations of this specificity have been performed. We aimed to handle this hole by using meta-analysis to offer a large-scale take a look at of the speculation that anxious apprehension is the dimension of tension most carefully related to enhanced ERN.

Though our predominant focus for the meta-analysis is on the ERN, we additionally report findings associated to the correct-response negativity (CRN). The CRN is a adverse ERP part noticed following right responses that has related topography, morphology, and maybe practical significance to the ERN (See Determine 1; Vidal et al., 2000, 2003; Bartholow et al., 2005). Some research have reported that nervousness is related to enhancement in total negativity following responses, together with each the ERN and CRN, suggesting overactive response monitoring basically (Hajcak and Simons, 2002; Hajcak et al., 2004; Endrass et al., 2008, 2010; Moser et al., 2012). Thus, you will need to examine how nervousness is said to the CRN. Furthermore, to isolate error-specific exercise from correct-related exercise, we examined the connection between nervousness and the distinction between the ERN and CRN—i.e., the ΔERN (see Weinberg et al., 2010, 2012a).

Supplies and Strategies

Research Choice

Revealed research inspecting the ERN and nervousness had been initially recognized utilizing the MEDLINE-PubMed and Google Scholar databases utilizing the phrases “nervousness,” “OCD,” “GAD,” “obsessive-compulsive,” “generalized nervousness,” “fear,” “motion monitoring,” “efficiency monitoring,” “battle monitoring,” “error-related negativity,” “Ne,” and “ERN.” Further research had been recognized from the reference sections of the articles obtained from the web searches and from contacting investigators for added unpublished datasets. This preliminary search yielded a complete of 75 research and datasets.

Inclusion/Exclusion Standards

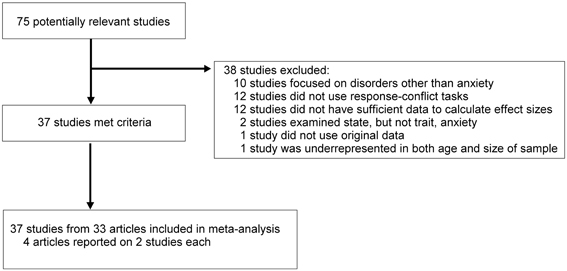

Determine 2 depicts the research choice course of used for the meta-analysis. Research had been included within the present meta-analysis if ERN information had been reported and so they included a measure that particularly recognized “nervousness” as the first assemble measured (e.g., the State-Trait Nervousness Stock—Trait Model; STAI-T) or others tapping carefully associated constructs comparable to behavioral inhibition (Behavioral Inhibition System scale; BIS). We did, nonetheless, exclude research by which nervousness was examined as secondary to a unique major psychopathology (e.g., secondary nervousness to a comorbid major alcohol use dysfunction; Schellekens et al., 2010). Furthermore, we centered on research of the response-locked ERN elicited in commonplace battle duties, such because the Eriksen flanker job (Eriksen and Eriksen, 1974), the Stroop job (Stroop, 1935), or variants of the Go/No-Go job. Past our motivations described above, this determination is additional justified by research exhibiting that enhanced ERN is uniquely related to OCD analysis and signs in such response battle duties (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2005; Gründler et al., 2009; Mathews et al., 2012). We excluded research utilizing trial-by-trial motivation manipulations. Research had been additionally excluded if we had been unable to compute a quantitative estimate (i.e., impact dimension) of the connection between nervousness and the ERN. One research (Cavanagh et al., 2010) was excluded as a result of it reported a re-analysis of information that had been included within the last meta-analysis (Gründler et al., 2009; Research 2 Flankers job). As a result of Moser et al. (2012) reported on a subset of the total pattern reported on in Moran et al. (2012) we solely included the Moran et al. (2012) research in order to incorporate the total pattern. Furthermore, we didn’t embrace the anxious arousal information from Moran et al. (2012) within the total evaluation, because the pattern is completely redundant with the anxious apprehension information, however we did embrace it carefully analyses described beneath.

Determine 2. Collection of research. Circulation chart depicting the collection of research used within the meta-analysis.

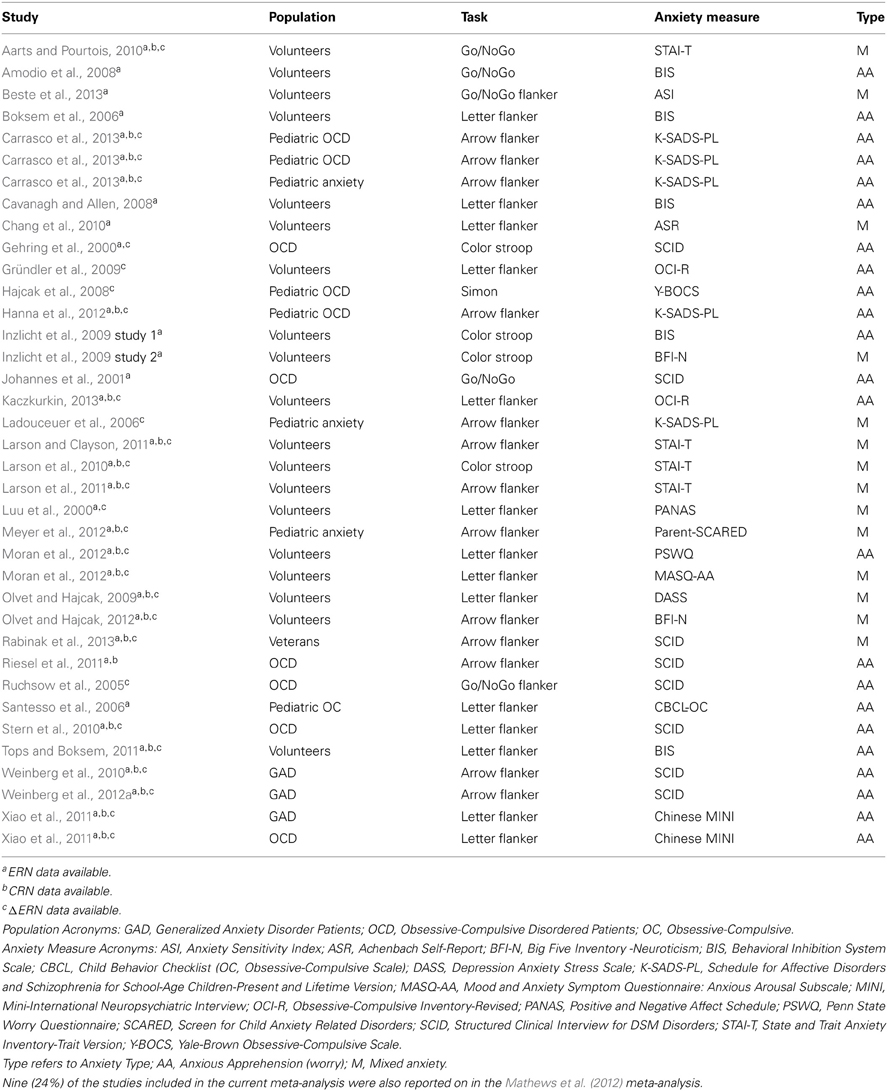

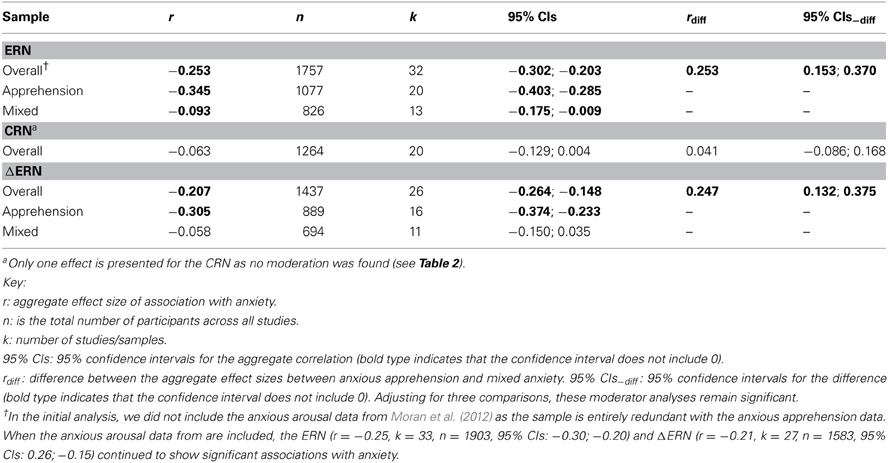

Utilizing our inclusion/exclusion standards, a complete of 37 research had been included within the current meta-analysis (see Desk 1). The collection of research was practically equally distributed amongst wholesome grownup volunteer samples (19; 51%) and anxiety-disordered samples (16; 43%), with the remaining two research utilizing samples with wholesome youngsters. Of the 37 research, 27 (73%) used a model of the Eriksen flanker job, 5 (14%) used a Go/NoGo job, 4 (11%) used the Coloration Stroop job, and 1 (2%) used the Simon job. There have been plenty of completely different self-report (and parent-report) measures of tension used within the last choice.

Desk 1. Traits of research included within the meta-analysis.

Overview of Analyses

For the current evaluation, we used the varying-coefficient mannequin beneficial by Bonett (2008, 2009, 2010) and Krizan (2010) as a result of (1) it doesn’t depend on the unrealistic assumptions made by different mounted results meta-analytic fashions (e.g., the existence of a single inhabitants impact dimension), (2) Bonett (2008, 2009, 2010) has demonstrated that varying-coefficient fashions present extra exact confidence intervals than different fashions, and (3) it performs properly within the presence of correlation heterogeneity and non-randomly chosen research (Bonett, 2008; c.f. Brannick et al., 2011). Synthesizer 1.0 (Krizan, 2010) was used for computing level estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

Pearson’s r was the focal impact dimension for all research fairly than Cohen’s d as the previous is extra in step with the concept nervousness is a steady dimension fairly than a definite class (Watson, 2005; Brown and Barlow, 2009). Cohen (1988) urged that rs ranging between |0.1| and |0.29| symbolize small results, rs ranging between |0.30| and |0.49| symbolize medium results and rs exceeding |0.50| are thought-about massive results. When deciphering the outcomes of the current analyses, it’s helpful to recall that error-monitoring ERPs are adverse deflections—that’s, a bigger ERN is one that’s extra adverse. Destructive correlations due to this fact point out that larger nervousness scores are related to a extra adverse deflection whereas a constructive correlation would point out that nervousness is related to a much less adverse deflection (i.e., a smaller ERN).

We tried to acquire information for all measures from all revealed research and identified unpublished datasets, however full protection was not attainable in all instances. Thus, most of the following analyses had been performed with subsets of the full variety of datasets.

The primary set of analyses aimed to quantify the general relationships between nervousness—broadly outlined—and ERN, CRN, and ΔERN. Impact sizes had been computed throughout research utilizing the reported associations between nervousness measures or teams and the ERN. Most research reported on a single anxiety-related measure or group. In another instances, investigators included multiple anxiety-related measure. In these instances, we selected the anxiety-related measure that was most persistently used throughout research in order to maximise the potential for comparability throughout research.

The focal analyses examined the speculation that anxious apprehension is the dimension of tension most carefully related to the ERN (in addition to the CRN and ΔERN). To do that, we created two teams of research based mostly on their measures of tension. The primary group was known as the “anxious apprehension” group, which included research of GAD and OCD diagnoses and signs in addition to research of the BIS. Our determination to incorporate the BIS within the anxious apprehension group was based mostly on 4 issues: (1) three of the seven objects (42%) making up the BIS measure utilized in ERN analysis embrace the phrase “fear” (Carver and White, 1994); (2) a latest large-scale research demonstrated that anxious apprehension (as measured by the Penn State Fear Questionnaire; PSWQ) was practically twice as extremely correlated with an avoidance motivation issue, together with a measure of BIS, than anxious arousal (as measured by the Temper and Nervousness Symptom Questionnaire—Anxious Arousal subscale; MASQ-AA; Spielberg et al., 2011); (3) information from our personal analysis workforce signifies that anxious apprehension correlates 3 times as extremely with BIS, itself, than anxious arousal and (4) current concept that hyperlinks BIS to anxious apprehension and battle between competing responses (Grey and McNaughton, 2000; Barlow, 2002; Amodio et al., 2008). The second group of research was known as the “blended” group, which included all different research. Our reasoning for grouping all different research collectively was that they concerned non-specific measures of anxiety-related constructs that always combine anxious apprehension with anxious arousal (e.g., the Nervousness Sensitivity Index; ASI) or mix nervousness with depression-related signs (e.g., STAI-T). To formally take a look at our differential specificity speculation, we in contrast the magnitude of the aggregated correlation coefficients between the anxious apprehension and blended research utilizing Synthesizer software program (Krizan, 2010).

Outcomes and Interim Dialogue

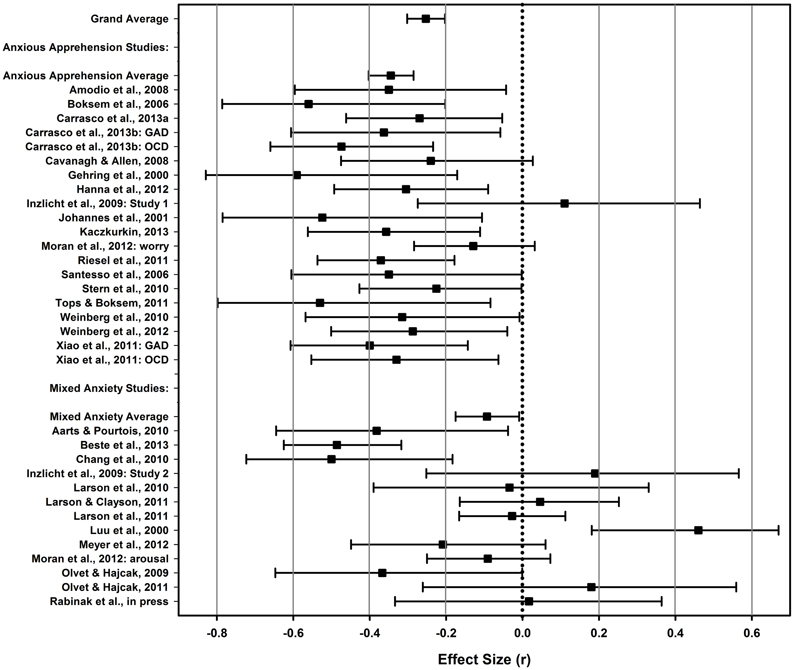

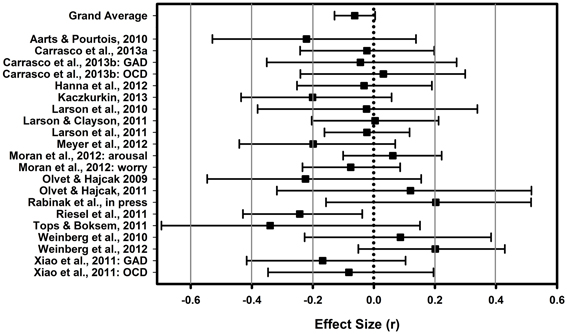

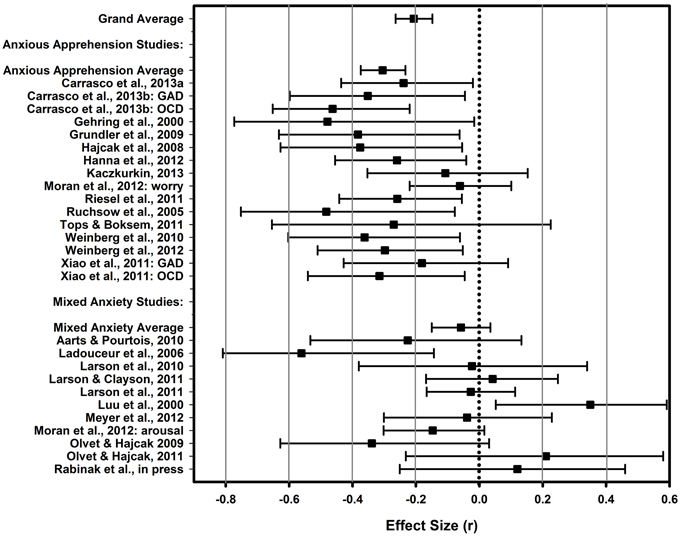

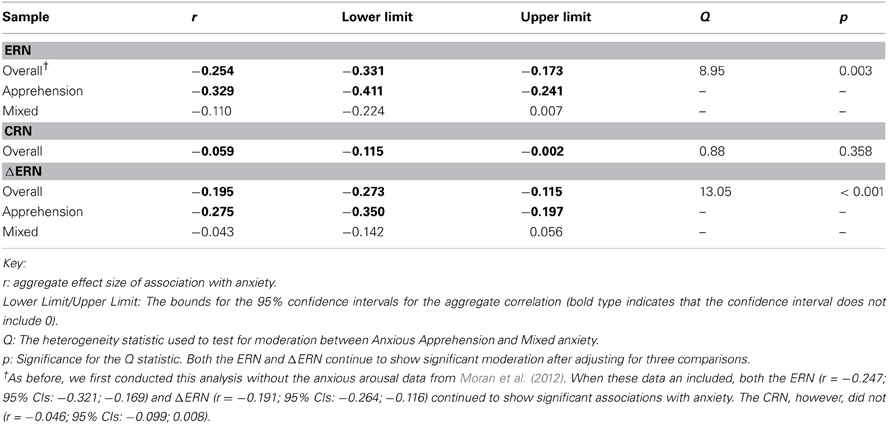

See Desk 2 for particulars of the outcomes. Total, we discovered that nervousness—broadly outlined—demonstrated a small to medium affiliation with the ERN and ΔERN. The CRN, nonetheless, was not reliably related to nervousness signs. Crucial to our focal speculation, we confirmed that anxious apprehension was extra strongly associated to enhanced ERN than non-specific, “blended,” types of anxiety-related signs (see Desk 2). The relationships between anxious apprehension and the ERN and ΔERN had been medium in dimension whereas the relationships between blended nervousness and the ERN and ΔERN had been fairly small (rs < 0.10). Outcomes from particular person research for the ERN, CRN, and ΔERN could be present in Figures 3–5, respectively. As could be gleaned from the figures, the blended nervousness research had been way more variable of their impact sizes, with many research exhibiting very massive confidence intervals as properly. Estimates of the CRN impact sizes had been likewise fairly variable and, in all however one research, demonstrated non-significant outcomes. Collectively, these outcomes assist the notion that the affiliation between error-related mind exercise and anxious apprehension is strong whereas the affiliation with much less particular types of nervousness is considerably weaker. Furthermore, given the non-specific nature of the measures employed within the “blended” research, it is usually attainable that any associations we detected could, in actual fact, be pushed by the anxious apprehension-related objects.

Desk 2. Outcomes from the meta evaluation.

Determine 3. ERN forest. A forest plot depicting impact sizes (r) between the ERN and measures of tension for the meta-analytic common (high), the anxious apprehension and blended nervousness averages, and particular person research. Error bars depict the 95% confidence interval for the impact dimension. The dotted line signifies an impact dimension of 0.

Determine 4. CRN forest. A forest plot depicting impact sizes (r) between the CRN and measures of tension for the meta-analytic common (high) and particular person research. Error bars depict the 95% confidence interval for the impact dimension. The dotted line signifies an impact dimension of 0.

Determine 5. ΔERN forest. A forest plot depicting impact sizes (r) between the ΔERN and measures of tension for the meta-analytic common (high), the anxious apprehension and blended nervousness averages, and particular person research. Error bars depict the 95% confidence interval for the impact dimension. The dotted line signifies an impact dimension of 0.

One concern is that almost all research performed with affected person samples had been included within the anxious apprehension group thus probably conflating the dimension of tension beneath research with affected person standing. To handle this subject, we examined moderation for the ERN utilizing non-patient research; the blended nervousness group contained solely a single affected person research thus precluding our capacity to check moderation for the affected person research. After eradicating affected person research, anxious apprehension research (r = −0.301, okay = 8; n = 410; 95% CIs: −0.400; −0.195) continued to point out larger impact sizes than blended nervousness research (r = −0.101, okay = 12, n = 794; 95% CIs: −0.186; −0.016; rdiff = 0.199; 95% CIs for the distinction: 0.064; 0.349). Subsequently, the distinction in impact sizes between the anxious apprehension vs. blended nervousness research can’t be accounted for by affected person research alone.

All advised, the outcomes of the present meta-analysis point out that nervousness, broadly outlined, demonstrates a small to medium affiliation with ERP indices of error monitoring. Most significantly, the findings are in step with the speculation that an enhanced ERN is extra strongly related to the anxious apprehension dimension of tension versus different anxiety-related constructs. Particularly, associations between anxious apprehension and ERN and ΔERN had been greater than 3 times as massive as these with different types of nervousness. In distinction, nervousness confirmed no dependable affiliation with the CRN, regardless of the best way by which nervousness was operationalized. This discovering offers essential data for creating mechanistic fashions of the hyperlinks between nervousness and error monitoring. Earlier than detailing a conceptual framework to know these findings, nonetheless, it’s helpful to level out caveats relating to the present meta-analysis and current a couple of sensible issues for future analysis.

First, the present meta-analysis included a comparatively small variety of research. Nonetheless, that is the primary meta-analysis of its variety and the full variety of research (N = 37) is consistent with earlier meta-analyses of associations between psychopathology and ERPs (e.g., Polich et al., 1994; Bramon et al., 2004; Mathews et al., 2012). Second, the precision of impact dimension estimates will even be improved if researchers acquire bigger samples than have sometimes been used on this literature thus far (pattern sizes within the present evaluation had been as little as n = 18; Median = 40, SD = 40.49), particularly as a result of most impact sizes within the social sciences are comparatively small (Cohen, 1988; Richard et al., 2003).

Third and most significantly, the duty of pin-pointing the affiliation between kind of tension and error monitoring has obtained restricted consideration within the literature. Most research have taken a extra world strategy by specializing in people with signs of GAD or OCD, or by contemplating associations between comparatively generic nervousness signs and error monitoring ERPs. We’re conscious of solely two research which have tried to empirically isolate particular relationships between sides of tension and error monitoring: our latest research (Moser et al., 2012) exhibiting that anxious apprehension was extra associated to enhanced ERN than anxious arousal and Hajcak and colleagues’ (2003) research exhibiting that top anxious apprehensive college students confirmed enhanced ERN in comparison with spider phobic college students. With the present meta-analysis we aimed to considerably lengthen this line of analysis. Nonetheless, as a result of so little information exist that parse dimensions of tension in relation to the ERN, we needed to create teams of research, a lot of which included total measures that faucet quite a lot of anxiety-related constructs.

We acknowledge that we took a conservative strategy to classifying the content material of particular measures and in contrast research that used pretty clear measures of anxious apprehension—GAD and OCD-related measures—to all others. It’s evident from the impact dimension estimates and figures that there’s way more consistency of constructive findings within the research utilizing extra exact measures of anxious apprehension. Ideally, there can be extra research immediately evaluating ERN magnitudes throughout teams of individuals created utilizing focused devices of various nervousness constructs—e.g., anxious apprehension vs. anxious arousal. This can be a problem we hope future analysis will undertake, as it’s not solely necessary to the present subject but in addition to constructing a extra biologically knowledgeable rubric for psychological dysfunction classification (cf. Cuthbert and Insel, 2010; Sanislow et al., 2010). On this means, our present analyses construct on seminal work by Heller and colleagues that has differentiated anxious apprehension from anxious arousal throughout psychometric and physiologic research (Heller et al., 1997; Nitschke et al., 1999, 2001; Engels et al., 2007; Silton et al., 2011; Spielberg et al., 2011).

Within the subsequent part, we use the outcomes of this meta-analysis as a place to begin for constructing a conceptual framework to elucidate why anxious apprehension/fear is the dimension of tension most carefully related to enhanced ERN. In brief, we suggest a compensatory error-monitoring speculation to elucidate the affiliation between nervousness and enhanced ERN. Our core declare is that enhanced ERN in nervousness outcomes from the interaction of a lower in processes supporting lively objective upkeep, due to the distracting results of fear, and a compensatory improve in processes (e.g., effort) devoted to transient reactivation of job objectives on an as-needed foundation when errors happen.

Dialogue

The Compensatory Error Monitoring Speculation

Our conceptual framework is an extension of current affective-motivational fashions of the affiliation between anxiety-related constructs and enhanced ERN (Luu and Tucker, 2004; Pailing and Segalowitz, 2004; Weinberg et al., 2012a,b). The inspiration of our account rests on 4 key findings about nervousness and cognitive operate: (1) that anxious apprehension/fear is considerably concerned in cognitive abnormalities in nervousness, (2) that anxious efficiency is characterised by processing inefficiency, (3) that enhanced ERN in nervousness is noticed with out corresponding deficits in job efficiency, and (4) that people with nervousness exhibit enhanced transient “reactive” management however decreased preparatory “proactive” management. We additional incorporate the battle monitoring concept of the ERN (Yeung et al., 2004) with the intention to forged the anxiety-ERN relationship in additional mechanistic phrases.

The function of anxious apprehension/fear

The current proposal builds on our earlier rationalization for why anxious apprehension exhibits a very sturdy affiliation with enhanced ERN (Moran et al., 2012; Moser et al., 2012), which in flip drew closely on Eysenck and colleagues’ (2007) Attentional Management Principle (ACT). ACT is a latest extension of Eysenck and Calvo’s (1992) authentic Processing Effectivity Principle (PET), which itself drew on Sarason’s (1988) earlier Cognitive Interference Principle. What all of those theories have in frequent is their emphasis on the deleterious results of anxious apprehension on cognition. That’s, all posit that distracting worries intrude with the flexibility of anxious people to remain centered on affectively impartial cognitive duties. These early theories had been supported by a number of research exhibiting the precise results of fear on cognitive efficiency (e.g., Morris et al., 1981).

ACT elevated specificity of the sooner work by proposing that nervousness is related to a deficit in attentional management that outcomes from an imbalance in exercise between the frontal goal-directed consideration system—involved with objectives and plans—and the parietal stimulus-driven consideration system—involved with salience and menace. Particularly, the ACT means that anxious people are characterised by enhanced exercise of the stimulus-driven consideration system and decreased performance of the goal-driven system. Anxious people are due to this fact tuned to prioritize salient inner (e.g., fear) and exterior (e.g., indignant face) sources of potential menace on the expense of affectively-neutral task-relevant stimuli. When no supply of exterior menace or distraction is current (e.g., throughout efficiency of an ordinary battle job) fear is distracting and more likely to deplete goal-driven assets. Our preliminary formulation of the anxiety-ERN relationship (Moran et al., 2012; Moser et al., 2012) utilized this frequent assertion that the fear part of tension is liable for cognitive processing abnormalities in affectively-neutral duties, utilizing this concept to elucidate that this nervousness dimension, particularly, is most carefully associated to the ERN.

The notion that nervousness’s affect on cognitive efficiency is primarily the results of the distracting results of fear additionally seems because the cornerstone of labor by Beilock and colleagues (Beilock and Carr, 2005; Beilock, 2008) who research relationships between nervousness and tutorial efficiency. Beilock (2008, 2010) means that fear co-opts out there working reminiscence assets that may in any other case be allotted to the duty at hand. Their work has demonstrated that quite a lot of varieties of tutorial nervousness—from math nervousness to spatial nervousness (Ramirez et al., 2012)—impair efficiency due to fear’s drain on assets. Thus, there may be important precedent from quite a lot of researchers for specializing in the distinctive results of fear on cognition in nervousness.

Nervousness is related to processing inefficiency

As initially famous by Eysenck and Calvo (1992) of their seminal assessment paper on Processing Effectivity Principle, anxious people typically carry out simply in addition to their non-anxious counterparts. The rationale efficiency is spared, they urged, is that anxious people make use of compensatory effort as a result of, though worries are distracting, in addition they inspire anxious people to beat the adverse results of their nervousness on efficiency. This dual-pathway compensatory effort thought helped to reconcile inconsistencies within the literature relating to the results of tension on efficiency.

How did they arrive to hypothesize the function of compensatory effort? First, Eysenck and colleagues confirmed that nervousness is commonly associated to longer response instances, however intact accuracy, throughout a spread of reasoning, studying, consideration, and dealing reminiscence duties (as reviewed by Eysenck and Calvo, 1992 and later once more by Eysenck et al., 2007). Thus, to realize the identical stage of efficiency accuracy appears to require anxious people to deploy enhanced effort and processing assets that take longer to implement. Second, their critiques confirmed that anxious people additionally self-report utilizing extra effort on duties by which they carry out on the similar stage as non-anxious people. PET and ACT due to this fact counsel that nervousness is related to processing inefficiency—extra effort or assets allotted to realize comparable stage of accuracy—however not essentially ineffectiveness (i.e., low accuracy).

Extra just lately, neuroimaging research have supplied further assist for the declare that enhanced processing assets (compensatory effort) assist anxious people keep typical ranges of efficiency (for a assessment see Berggren and Derakshan, 2013). For instance, enhanced dorsolateral prefrontal cortex exercise was reported on incongruent relative to congruent Stroop trials in a pattern of anxious school college students (Basten et al., 2011). Equally, enhanced NoGo N2 was reported in anxious college students regardless of comparable efficiency to non-anxious college students (Righi et al., 2009). Berggren and Derakshan (2013) summarized plenty of further consonant results—i.e., larger processing assets and compensatory effort revealed in anxious people regardless of comparable behavioral efficiency –throughout a spread of consideration and reminiscence paradigms.

As well as, a latest neuroimaging research confirmed that nervousness’s deleterious impact on math efficiency was curtailed to the extent that top math anxious individuals recruited frontal management mind areas (Lyons and Beilock, 2011). Thus, the impression of tension on tutorial efficiency was mitigated by compensatory cognitive management—exactly as PET/ACT would predict. There’s due to this fact sturdy assist for the notion that anxious people can carry out in addition to non-anxious people; nonetheless, they draw on extra processing assets and energy to take action.

Immediately associated to the ERN, processing inefficiency offers a proof for a curious discovering from Endrass et al. (2010) who confirmed that though non-anxious management individuals demonstrated an enhanced ERN throughout a punishment situation, OCD sufferers didn’t. Particularly, ACT (Eysenck et al., 2007) predicts that motivational manipulations ought to have minimal impression on anxious people as a result of compensatory effort is already being employed throughout baseline efficiency whereas such manipulations ought to trigger will increase in efficiency in non-anxious people as a result of they allocate extra effort to realize the inducement. Certainly, Eysenck and colleagues demonstrated this impact in early behavioral work (as reviewed in Eysenck et al., 2007). On this mild, Endrass and colleagues’ (2010) outcomes counsel that enhanced ERN in non-anxious people throughout punishment mirrored elevated compensatory error monitoring that was already at ceiling within the OCD group throughout the usual situation.

Enhanced ERN in nervousness is noticed within the absence of compromised efficiency

In step with PET/ACT and the above-reviewed research, anxious people appear to show typical ranges of efficiency in the usual battle duties utilized in ERN research. But, they persistently present enhanced ERN. Certainly, solely three particular person research of the 37 included within the current meta-analysis of the ERN reported a big relationship between nervousness and error fee. A binomial take a look at means that that is in step with a 5% false constructive fee (z = 1.02, p = 0.16). Furthermore, no particular person research reported a big relationship between nervousness and response time.

To additional consider this subject, we performed a further meta-analysis on error fee and response time for these research reported on in our meta-analysis of the ERN. As we did with the ERN, we first performed the meta-analysis throughout all research for which we might calculate impact sizes. Then, we performed moderation evaluation by nervousness kind. This evaluation yielded no important relationship between nervousness (throughout all research) and error fee (okay = 29; N = 1668; r = −0.02, 95% CIs: −0.08; 0.03). There was, nonetheless, important moderation by nervousness kind such that anxious apprehension was related to decrease error fee (r = −0.08; 95% CIs: −0.15; −0.004) and blended nervousness was related to non-significantly greater error fee (r = 0.08; 95% CIs: −0.02; 0.18; rdiff = 0.16, 95% CIs for the distinction: 0.04; 0.28). Each of those results are notably small in magnitude. With regard to total response time, there was no important impact of tension (okay = 26; N = 1480; r = −0.06, 95% CIs: −0.12; 0.002), nor was there any important proof of moderation (rdiff = 0.09; 95% CIs: −0.05; 0.23). Collectively, these findings counsel the small-to-medium affiliation between nervousness (throughout all research) and the ERN is noticed within the absence of altered behavioral efficiency. Importantly, the associations between error fee and anxious apprehension and blended nervousness unlikely contribute to ERN results, as they emerge as small results and in opposing instructions for the 2 nervousness sorts.

Thus, consistent with the notion that nervousness is characterised by processing inefficiency, we recommend that enhanced ERN in nervousness could index a compensatory effort sign geared toward sustaining an ordinary stage of efficiency (Moran et al., 2012; Moser et al., 2012). That’s, enhanced ERN associated to nervousness displays inefficient error monitoring, in that anxious people could depend on larger error monitoring assets to realize the identical stage of efficiency as non-anxious people. Collectively, then, we recommend that the precise distracting results of fear throughout affectively-neutral battle duties requires anxious people to interact in compensatory effort to carry out as much as par, with enhanced ERN being one index of this compensatory effort/larger utilization of processing assets.

Nervousness is related to enhanced reactive management, however decreased proactive management

Braver (2012) and colleagues’ (Braver et al., 2007) twin mechanisms of management (DMC) mannequin offers one other appropriate context by which to know the function of enhanced ERN as a compensatory effort sign in nervousness. The DMC mannequin means that cognitive management is achieved by way of two distinct modes: proactive and reactive. Proactive management—the extra cognitively taxing of the 2 modes—includes lively upkeep of guidelines and objectives inside lateral areas of prefrontal cortex in a preemptive trend to facilitate future efficiency. In distinction, reactive management—the much less effortful mode—includes allocating consideration to guidelines and objectives on an as-needed foundation, as soon as an issue (such because the prevalence of battle or an error) has arisen. Moreover, Braver (2012) refers to reactive management as a “‘late correction’ mechanism” (p. 106) and hyperlinks it to exercise of the ACC, such that ACC-mediated battle monitoring could assist people reactivate job objectives in a transient, as-needed trend. The DMC mannequin is due to this fact instantly related to the present dialogue as a result of it immediately parallels the main target of ACT on the interplay between goal-driven (or proactive management) and stimulus-driven (or reactive management) consideration methods (Eysenck et al., 2007).

In accordance with Braver (2012), non-anxious people are in a position to alternate flexibly between reactive and proactive management modes in accordance with altering job calls for. In distinction, Braver (2012) means that anxious people are distracted by worries that deplete assets wanted for lively objective upkeep, thereby interfering with proactive management and throwing chronically anxious people right into a reactive management mode. That’s, anxious people rely extra closely on reactive management. Growing proof helps this propensity for anxious people to preferentially interact in reactive management (Grey et al., 2005; Fales et al., 2008; Krug and Carter, 2010, 2012). For instance, Fales et al. (2008) confirmed that anxious people demonstrated decreased sustained, however elevated transient, exercise in working reminiscence areas in step with the notion of decreased proactive and elevated reactive management.

A latest research by Nash et al. (2012) exhibiting that elevated behavioral activation system (BAS) exercise, as listed by left-sided prefrontal EEG asymmetry, was related to a decreased ERN offers further assist for our proposed differential results of proactive and reactive management on ERN. Certainly, BAS has been related to proactive management and decreased dACC/MCC exercise (see Braver et al., 2007 for a assessment). Thus, whereas nervousness/BIS is related to reactive management and due to this fact an enhanced ERN—as demonstrated in our meta-analysis—BAS is related to proactive management and due to this fact a decreased ERN.

Formalizing the mannequin utilizing the battle monitoring concept of the ERN

We undertake the battle monitoring concept of the ERN and its latest extensions (Yeung and Cohen, 2006; Steinhauser and Yeung, 2010; Hughes and Yeung, 2011; Yeung and Summerfield, 2012) in order to leverage a well-articulated computational mannequin of the ERN to assist clarify the connection between nervousness and enhanced ERN. In accordance with the battle monitoring concept, the ERN displays battle that’s detected when continued goal processing after an error results in activation of the right response, leading to battle with the error simply produced. This notion is rooted within the basic discovering that people are likely to routinely right their errors on account of continued stimulus processing (Rabbitt, 1966; Rabbitt and Vyas, 1981). Thus, the ERN indexes processes concerned within the speedy correction of errors that displays the present stage of cognitive demand or effort—i.e., the extent of response battle (see additionally Hughes and Yeung, 2011; Yeung and Summerfield, 2012). Within the context of broader theories of the ACC—the neural supply of the ERN—the ERN offers details about present conflicts with the intention to optimize motion choice and habits (Botvinick et al., 2001; Botvinick, 2007). The battle monitoring concept of the ERN properly dovetails with the DMC in that each counsel the ACC is concerned in reactive management, insofar because the ERN displays ACC-mediated battle monitoring arising from activation of the error-correcting response (Yeung and Summerfield, 2012)—i.e., a late correction mechanism.

Thus, our compensatory error-monitoring speculation of enhanced ERN in nervousness first attracts on the above reviewed concept and proof in assuming that nervousness will increase sustained consideration to inner sources of menace (i.e., fear) thereby lowering out there assets devoted to lively upkeep of job guidelines and objectives. Consequently, the anxious particular person is pressured to depend on reactive management as a compensatory technique. Critically, when errors happen, reactive management causes a rise in stimulus processing round and after the time of the wrong response, resulting in enhanced battle between the just-produced error and the right (goal) response that provides rise to an enhanced ERN (Yeung et al., 2004). Detection of this battle might then assist to reactivate job objectives within the second and normalize efficiency in anxious people (Braver, 2012). At the very least with respect to battle duties, this dynamic appears to offer a mechanistic account of an enhanced ERN within the presence of comparable efficiency amongst anxious people, as a result of the interactive results of decreased proactive management and elevated reactive management would cancel one another out on the behavioral stage. Having detailed our compensatory error-monitoring speculation, we now flip to new sources of proof that present further assist for our claims.

New sources of assist for the compensatory error-monitoring speculation

Our compensatory error-monitoring speculation largely hinges on two concepts: (1) that the cognitive load of fear begins a cascade of processes that result in enhanced ERN in anxious people, and (2) enhanced ERN in nervousness displays a compensatory consideration/effort response. On this part, we current information from our personal lab that gives extra direct assist for these underlying assertions of our mannequin.

If enhanced ERN in nervousness outcomes from the cognitive load of worries on processing assets, it follows that experimentally induced cognitive load also needs to result in enhanced ERN. Latest experimental information from our lab helps this notion that cognitive load—an affectively-neutral analog to distracting worries—enhances the ERN. In a research by Schroder et al. (2012), we confirmed that the ERN is enhanced when stimulus-response guidelines are switched, ensuing within the want for people to concurrently inhibit previous guidelines and keep present guidelines. We urged that on account of this have to juggle previous and present guidelines, a cognitive load was positioned on topics throughout trials by which stimulus-response guidelines had been switched. When errors occurred, then, compensatory attentional effort was employed as a reactive management technique leading to enhanced ERN.

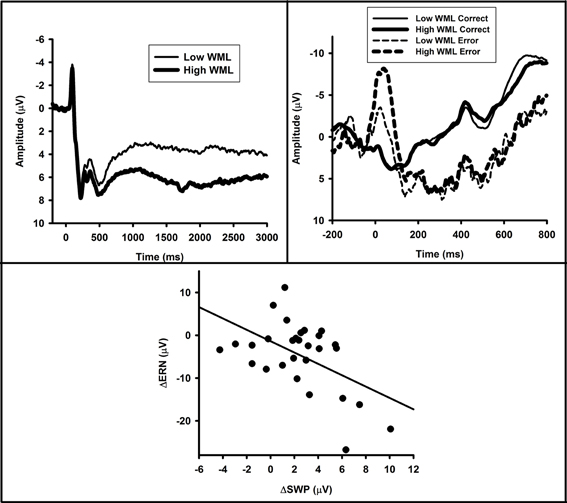

Extra immediately, we performed an experiment inspecting the impact of verbal working reminiscence load (WML) on the ERN (Moran and Moser, 2012), the main points of which we current right here. Twenty-nine undergraduates (21 Feminine, M age = 19.52 years, SD = 2.72) accomplished a flanker job interleaved with a successor-naming job (for the same technique, see (Lavie and Defockert, 2005): Experiment 2). Prior to every flanker stimulus, individuals noticed a string of 5 numbers to recollect. Every five-number string was both in numerical order (low WML) or in a random order (excessive WML). Members had been instructed to memorize these digits. Following every flanker stimulus, a reminiscence probe, which consisted of a randomly-selected quantity from the five-number reminiscence set, was offered and individuals had been instructed to enter the digit that adopted the reminiscence probe digit within the reminiscence set for that trial. The experimental session consisted of 480 trials grouped into six blocks. Load was randomly diverse by block such {that a} given block contained just one kind of WML. There have been an equal variety of high- and low-WML blocks. The ERN (and CRN) elicited by flanker errors was calculated as the typical exercise within the 0–100 ms post-response time window relative to a −200 to 0 ms pre-response baseline at FCz. ERN/CRNs had been then submitted to a 2 (Accuracy: Error vs. Right) × 2 (WML: Excessive vs. Low) repeated-measures evaluation of variance (ANOVA).

Of key curiosity was the prediction that ERN amplitude must be elevated in circumstances of elevated WM load. The principle impact of accuracy [F(1, 28) = 39.54, p < 0.01, η 2p = 0.59] confirmed the presence of a transparent ERN on this paradigm. Crucially, and in step with our speculation, the WML × accuracy interplay was important [F(1, 28) = 9.69, p < 0.01, η 2p = 0.28; See Figure 6 top right panel]. The ERN was enhanced on excessive load trials [t(28) = 3.50, p < 0.01] whereas the CRN was unaffected by the WML manipulation (t < 1). Furthermore, the ERN-CRN distinction wave was larger on excessive WML trials than low WML trials [t(28) = 3.11, p < 0.01].

Determine 6. Working reminiscence load enhances ERN. (Prime Left) SWPs elicited through the reminiscence retention interval. (Prime Proper) Response-locked ERPs as a operate of accuracy and WML. (Backside) A scatterplot depicting the affiliation between WM-related adjustments in SWPs and ERNs.

To check the prediction that particular person variations in sensitivity to load ought to correlate with adjustments in ERN amplitude, we additionally correlated the ERN with a well-validated ERP index of WM-retention. Specifically, we measured the left-anterior constructive slow-wave potential (SWP) that exhibits larger magnitude on high- vs. low-WML trials (Ruchkin et al., 1997; Berti et al., 2000; Kusak et al., 2000). By inspecting the connection between the SWP (WM-retention) and the ERN, we supposed to offer proof that occupying WM capabilities beneath load, like fear, immediately results in elevated ERN. The SWP was computed throughout the five hundred–3000 ms post-stimulus window with respect to a baseline consisting of the typical exercise within the 200 ms window instantly previous to the presentation of the reminiscence set. The SWP was quantified as the typical exercise recorded at F3. SWPs had been submitted to a single-factor (WML: Excessive vs. Low) repeated-measures ANOVA.

In step with earlier work, excessive WML reminiscence units elicited larger left-anterior positivity than low WML reminiscence units through the rehearsal interval [F(1, 28) = 18.21, p < 0.01, η 2p = 0.39; see Figure 6 top left panel]. To immediately hyperlink WM operations with the ERN, we first computed WM-related adjustments for every of our measures: ΔERN was computed because the ERN-CRN distinction on excessive WML trials minus the ERN-CRN distinction on low WML trials—that’s, the extent to which error-related mind exercise was modulated by the WML manipulation; ΔSWP was computed because the distinction in exercise between excessive and low WML trials throughout memory-set presentation. We centered on the ERN-CRN distinction as a result of important Accuracy × WML interplay. Nonetheless, if we compute ΔERN because the ERN on high-WML trials minus the ERN on low-WML trials the interpretation of the outcomes doesn’t change. Critically, findings revealed that ΔERN was strongly associated to ΔSWP (r = −0.51, p < 0.01) indicating that enhanced ERN beneath excessive WML could be attributed to elevated WM operations throughout rehearsal (Determine 6 backside panel). Such information present notably sturdy causal proof that present cognitive load results in enhanced ERN. Collectively, they supply a proof-of-concept for the notion that the improved ERN that characterizes nervousness could end result from WML imposed by fear.

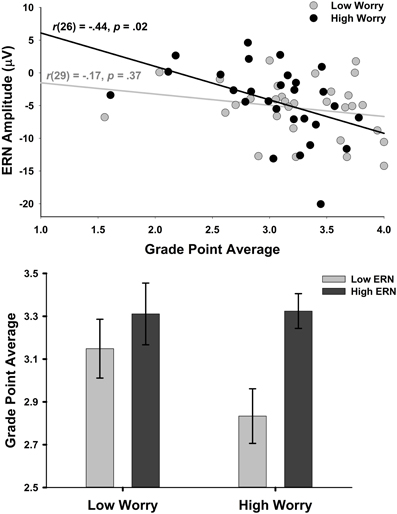

Concerning our assertion that enhanced ERN in nervousness displays a compensatory consideration/effort response, we current outcomes from a novel evaluation inspecting associations between anxious apprehension, ERN, and tutorial efficiency—as measured by grade-point common (GPA)—on a subsample of information from a bigger dataset (Moran et al., 2012). Previous work has proven that bigger ERN amplitudes correlate with greater GPA, suggesting that enhanced cognitive management is related to greater tutorial achievement (Fisher et al., 2009; Hirsh and Inzlicht, 2010). Nonetheless, no research have examined whether or not nervousness moderates this relationship. We predicted that if enhanced ERN in anxious apprehension displays a reactive compensatory management sign, a bigger ERN in worriers must be related to greater GPA. Following this logic, a low ERN in worriers can be related to poorer tutorial efficiency. If, alternatively, the ERN just isn’t associated to compensatory management in nervousness, the ERN-GPA relationship mustn’t differ as a operate of tension.

We examined these predictions in 59 undergraduates (24 feminine, M age = 20 years, SD = 3.20) who had useable cumulative GPA information collected from the College’s Workplace of the Registrar. EEG recording procedures and job descriptions have been described elsewhere (Moran et al., 2012); individuals engaged in a letter flanker job after which accomplished the Penn State Fear Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer et al., 1990). The ERN was calculated as the typical exercise within the 0–100 ms post-response time window relative to a −200 to 0 ms pre-response baseline correction at FCz (the place it was maximal) on error trials.

In step with earlier work (Hirsh and Inzlicht, 2010), bigger ERN amplitude was considerably correlated with greater GPA throughout the entire pattern (r = −0.30, p < 0.05). Nonetheless, the connection was small and non-significant amongst people beneath the median on PSWQ scores (Low Worriers, n = 31; r = −0.17, p = 0.37) however was important and greater than double the scale amongst these above the median on the PSWQ (Excessive Worriers, n = 28; r = −0.44, p < 0.05, see Determine 7). To discover additional the relationships between fear, ERN amplitude, and GPA, the median scores on the PSWQ (Median = 51.00) and ERN (Median = −4.42 μV) had been used to categorize individuals into one in all 4 teams: Low Fear—Low ERN (n = 13), Excessive Fear—Low ERN (n = 16), Low Fear-Excessive ERN (n = 18), and Excessive Fear—Excessive ERN (n = 12). A one-way evaluation of variance (ANOVA) with Fear-ERN Group because the between-subjects issue and cumulative GPA because the dependent variable revealed a big impact of Group [F(3, 58) = 3.17, p = 0.03]. This impact is depicted in Determine 7. Fisher’s least important distinction process indicated that individuals within the Excessive Fear-Excessive ERN group had a considerably greater GPA (M = 3.32, SD = 0.53) than the Excessive Fear-Low ERN group (M = 2.83, SD = 0.51; p < 0.05) and that the Low Fear-Excessive ERN group (M = 3.31, SD = 0.61) additionally had a considerably greater GPA than the Excessive Fear-Low ERN group (p < 0.01). The distinction between the Low Fear-Low ERN group (M = 3.15, SD = 0.50) and Excessive Fear-Low ERN group was marginal (p = 0.10). Critically, the Excessive Fear-Excessive ERN and Low Fear-Excessive ERN teams didn’t differ on GPA (p > 0.90).

Determine 7. Relationship between ERN and GPA is moderated by fear. (Prime) Scatterplot exhibiting the connection between ERN and GPA within the high 50% of the PSWQ distribution (black) and the underside 50% (grey). (Backside) Bar graph depicting GPA as a operate of ERN and Fear teams which had been created by median splits and described within the textual content. Error bars symbolize commonplace error of the imply.

Collectively, these exploratory analyses present additional proof that enhanced ERN amongst worriers capabilities as a compensatory management sign insomuch as worriers with a big ERN achieved the identical GPA as non-worriers. In distinction, people with excessive fear and a low ERN, suggesting a scarcity of effortful compensatory management, tended to have considerably poorer tutorial achievement. Though preliminary, these findings are in step with the Lyons and Beilock (2011) research exhibiting that nervousness’s deleterious impact on math efficiency was curtailed to the extent that top math anxious individuals recruited frontal management mind areas.

Predictions and Instructions for Future Analysis

Thus far, we’ve got supplied theoretical rationale and empirical proof for our compensatory error-monitoring speculation of the affiliation between anxious apprehension and enhanced ERN. On this subsequent part, we develop a set of further predictions and key avenues for future analysis to pursue.

The primary, and maybe most evident, prediction for future analysis to check is that inducing fear ought to result in an enhancement of the ERN. Borkovec and Inz (1990) have developed and carried out an ordinary fear induction process for many years that might be simply utilized within the context of an ERN research. Earlier nervousness inductions have demonstrated adverse outcomes with regard to their results on the amplitude of the ERN. For example, Moser et al. (2005) induced concern in spider phobic undergraduates and confirmed no impact on ERN magnitude. Equally, Larson et al. (2013) failed to point out an impact of an nervousness induction on ERN magnitude. Our prediction is that enhanced ERN will solely be elicited to the extent that anxious apprehension—fear—is induced. The failure of current research to search out results of tension induction on ERN could due to this fact be the results of their use of anxious arousal inductions as an alternative of fear inductions.

Equally, we predict that worries captured at ERN testing ought to relate to enhanced ERN and will mediate the affiliation between trait fear and enhanced ERN. Particularly, on- and/or off-task worries might be measured following flanker efficiency and associated to the ERN. If worries throughout job efficiency are liable for co-opting goal-driven assets and inflicting compensatory deployment of reactive management assets, then such measures of fear ought to relate to enhanced ERN. The Cognitive Interference Questionnaire (CIQ; Sarason and Stoops, 1978; Sarason et al., 1986) can be one measure of this assemble price exploring on this regard. Self report and thought sampling strategies for measuring thoughts wandering and task-unrelated ideas (Matthews et al., 1999; Schooler et al., 2011; Mrazek et al., 2011, 2013) would even be necessary for future assessments of our hypotheses.

Following from our formulations and the preliminary findings of Endrass et al. (2010), we’d additionally predict that incentive and motivation manipulations ought to have much less impact on ERN amplitude in anxious than non-anxious populations. There are quite a few methods to control incentive and motivation and thus this impact might be examined in quite a lot of contexts. Beforehand, Hajcak et al. (2005) confirmed that the amplitude of the ERN was enhanced on trials that had been price extra factors towards a financial incentive in addition to beneath a situation of efficiency analysis. We predict that such manipulations wouldn’t result in enhanced ERN in anxious people as a result of they already make use of compensatory effort throughout baseline circumstances.

Therapy research not solely supply the prospect to assist enhance anxious peoples’ functioning but in addition to check theory-derived hypotheses. With respect to our view that the anxiety-ERN relationship displays reductions in proactive management and compensatory will increase in reactive management, one therapy chance is to coach anxious people to undertake extra of a proactive management technique. Proactive management coaching has been efficiently carried out in people with schizophrenia, leading to decreased signs and extra proactive mind exercise (Edwards et al., 2010), in addition to in older adults who have a tendency to interact in reactive management methods earlier than, however not after, coaching (Braver et al., 2009; Czernochowski et al., 2010; Jimura and Braver, 2010). We predict that proactive management coaching in worriers would end in reductions in ERN magnitude which may additionally mediate the effectiveness of the intervention by way of symptom discount. Equally, one other chance for testing our speculation comes from Ramirez and Beilock’s (2011) latest demonstration that emotional expressive writing improves take a look at efficiency in excessive take a look at anxious people through its results on lowering worries and liberating up proactive assets for lively objective upkeep. We anticipate that expressive writing about worries would likewise end in decreased ERN magnitude in extremely apprehensive people.

A very thrilling function of this final set of predictions regarding therapy results on the ERN in anxious people is that it offers a context by which to interpret broader results of tension therapy on the ERN. So far, one research in pediatric OCD sufferers confirmed that the ERN didn’t change with profitable cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) of OCD (Hajcak et al., 2008). This research has been cited as proof for a “trait” biomarker or “endophenotype” interpretation of enhanced ERN in nervousness (e.g., Olvet and Hajcak, 2008). Nonetheless, there appear to be three issues with this conclusion: (1) regardless of symptom discount within the OCD sufferers, post-treatment scores nonetheless positioned them across the medical cutoff for an OCD analysis, (2) CBT is an intervention designed to cut back nervousness signs, not alter underlying neural mechanism concerned in cognitive management (i.e., ERN), and (3) the research was performed in youngsters and adolescents for whom the anxiety-ERN relationship could also be completely different than in adults (Meyer et al., 2012). On this means, although sufferers confirmed decreased OCD signs after therapy, they nonetheless demonstrated anxiety-related compensatory effort, as mirrored in enhanced ERN. The main focus of our predictions just isn’t on lowering nervousness signs per se, however fairly to vary the practical relationship between fear and cognitive functioning (cf. Ramirez and Beilock, 2011). For example, the aim of the expressive writing intervention is to focus on the mechanism concerned in nervousness’s results on cognition. This strategy won’t solely assist take a look at our predictions set forth right here however it might additionally inform therapies of tension and their impression on efficiency.

The present framework offers an necessary hyperlink between nervousness analysis and computational fashions of cognition. Thus, we recommend that future analysis on this space (and in different allied areas as properly) apply computational modeling to check predictions in regards to the associations between nervousness and error-monitoring ERPs and associated efficiency measures. Yeung and Cohen (2006), for example, demonstrated the facility of making use of computational modeling to know ACC-mediated monitoring deficits in lesion sufferers. Curiously, they confirmed that decreased ERN in sufferers with ACC lesions might be modeled as ensuing from impaired consideration management fairly than particular impairments in conflict-monitoring per se. Making use of this modeling method to the anxiety-ERN relationship, particularly by implementing distinct proactive and reactive management modes in a single mannequin (e.g., De Pisapia and Braver, 2006), represents an thrilling path for future analysis. This strategy may assist illuminate whether or not nervousness impacts ACC-mediated monitoring capabilities immediately, as envisioned in present theories that emphasize tight linkages between management and affective capabilities in ACC (e.g., Shackman et al., 2011; Hajcak, 2012), or fairly has an oblique impression by way of its results on cognitive management modes (e.g., Braver, 2012), as urged by our evaluation.

This framework additionally offers the inspiration for incorporating different conflict- and error-monitoring ERPs which have did not be adequately addressed by researchers primarily within the anxiety-ERN relationship. Concerning the CRN, for instance, the outcomes of the present meta-analysis counsel that it’s not reliably related to nervousness, thus failing to assist the notion of basic overactive motion monitoring in nervousness (e.g., Hajcak et al., 2003; Endrass et al., 2008). The error positivity (Pe)—a centro-parietally maximal ERP that follows the ERN (See Determine 1; Falkenstein et al., 2000)—is one other error-monitoring ERP that has obtained restricted consideration within the nervousness literature. The Pe seems to index specific error-related processing, together with the detection and signaling of errors (Yeung and Summerfield, 2012). So far, analysis is equivocal, with some research exhibiting decreased Pe (Moser et al., 2012), some exhibiting enhanced Pe (Weinberg et al., 2010) and nonetheless others exhibiting no affiliation (Weinberg et al., 2012a) in nervousness. Once more, such inconsistent findings argue towards a basic impairment in error/motion monitoring.

The N2, a fronto-central negativity noticed round 250–350 ms within the stimulus-locked ERP on right trials, is a related action-monitoring ERP that’s presupposed to mirror pre-response battle elicited by the co-activation of right and incorrect responses when stimuli are related to each (e.g., incongruent flanker stimuli; Yeung et al., 2004). Sadly, the N2 is much more ignored than the Pe in nervousness analysis. Two research, not included within the present evaluation as a result of they didn’t report ERN information, nonetheless, counsel enhanced N2 in trait anxious school college students (Righi et al., 2009; Sehlmeyer et al., 2010). If enhanced N2 had been to emerge as a dependable marker of tension in future research, it might counsel a extra basic impact of tension on battle monitoring (Yeung et al., 2004).

Associated Accounts of Enhanced ERN in Nervousness

The most important advance of our proposal is that it makes an attempt to immediately account for the connection between nervousness and the ERN. Though there exist emotional-motivational accounts of the ERN and its within- and between-subjects variation (Pailing and Segalowitz, 2004; Weinberg et al., 2012b), none make particular predictions in regards to the relationship between nervousness and the ERN. Fairly, current accounts are a lot broader of their assertions relating to the practical significance of the ERN and its variation throughout people. Nonetheless, to the extent that current emotional-motivational accounts could be utilized to the anxiety-ERN relationship, we subsequent deal with how they fare with regard to their capacity to elucidate current information.

Researchers have urged that the ERN is an affective or emotional response to errors (Luu and Tucker, 2004; Pailing and Segalowitz, 2004), largely due to associations famous between the ERN and particular person variations in emotional traits like nervousness. In accordance with this view, then, an enhanced ERN in anxious people displays their heightened adverse emotional response to or issues over errors (Bush et al., 2000; Gehring and Willoughby, 2002; Hajcak et al., 2005). Many earlier research pointed to each heightened ERN amplitude and overactive error-related ACC exercise in nervousness as proof of a dysfunctional affective response to errors, notably in people with OCD (Gehring et al., 2000; Johannes et al., 2001). Useful imaging proof exhibiting rostral ACC enhancement in response to errors in OCD sufferers (Fitzgerald et al., 2005) was thought-about sturdy assist for this declare, because the rostral subdivision is commonly thought-about the “affective/emotional” portion of ACC, versus the “cognitive” subdivision that lies dorsally (Bush et al., 2000).

A associated conceptualization means that variation within the magnitude of the ERN displays particular person variations in defensive reactivity (Hajcak and Foti, 2008; Hajcak, 2012; Weinberg et al., 2012a). That’s, the ERN carries data geared toward mobilizing assets to guard the organism towards subsequent adverse occasions, with this response being delicate to particular person variations in aversiveness of errors. These authors situate the ERN in a broader community of defensive motivational methods concerned in executing a cascade of physiological, cognitive, and behavioral responses when potential threats are detected (Lang et al., 1997; Bradley et al., 2001; Bradley, 2008). On this view, the ERN is a neural marker of a broader neurobehavioral trait—that’s, a secure particular person distinction with identifiable referents in neurobiology and habits (Patrick and Bernat, 2010; Patrick et al., 2012)—of defensive reactivity. Nervousness is included on this mannequin as reflecting particular person variations in defensive reactivity thereby supporting the idea’s major competition.

Though the affective response and defensive reactivity fashions present believable accounts of heightened ERN amplitude in nervousness, they solely loosely deal with the truth that some types of nervousness are extra carefully tied to enhanced ERN than others. Our conceptual framework, alternatively, makes use of this distinction as foundational for specifying the connection between nervousness and the ERN. There are additionally contradictory findings within the literature that time to further weaknesses in present approaches to conceptualizing the connection between nervousness and the ERN.

With regard to the affective response interpretation, the cognitive vs. affective subdivision mannequin of the ACC just isn’t supported by extant analysis (Shackman et al., 2011). Thus, it’s unclear whether or not enhanced rostral ACC activation following errors in anxious people is indicative of an affective response per se (cf. Poldrack, 2011 for issues with reverse inference basically). Fairly, as Shackman et al. counsel, such ACC activation in anxious people could mirror a extra area basic “adaptive management” response. Furthermore, modulations of ACC exercise shouldn’t be conflated with these of the ERN given the potential for a number of sources to contribute to the technology of the ERN (Gehring et al., 2012). Proof from our personal work additional demonstrates this level. Particularly, though ACC exercise is enhanced throughout symptom provocation in easy phobics (e.g., spider phobics; Rauch et al., 1995), we confirmed that the ERN just isn’t (Moser et al., 2005).

Concerning the defensive reactivity interpretation, proof talking on to the assertion that “… anxious people who’re characterised by elevated ERNs could exhibit a larger defensive response to errors in contrast with non-anxious people” (Hajcak and Foti, 2008, p. 106) is missing. The truth is, Endrass and colleagues’ (2010) failure to point out modulation of the ERN by punishment in an OCD pattern is inconsistent with a defensive reactivity account. If enhanced ERN in nervousness displays the aversiveness of errors, it stands to cause that the ERN ought to have been enhanced through the punishment situation within the OCD pattern. That this end result was not noticed suggests the aversiveness of the error didn’t considerably contribute to enhanced ERN within the OCD pattern in both the baseline or punishment situation. Riesel et al. (2012), alternatively, did discover that punishment enhanced the ERN in excessive trait anxious people however not low trait anxious people. Nonetheless, the authors utilized the STAI-T, which we’ve got proven right here just isn’t reliably related to enhanced ERN. Certainly, excessive STAI-T people within the Riesel et al. research didn’t present enhanced ERN within the management situation, solely a bigger enhancement of the ERN from the management to punishment situation. Taken collectively, extant information are equivocal as to the flexibility of the defensive reactivity account to elucidate enhanced ERN in nervousness.

Concluding Remarks

Our overarching objective on this paper has been to offer a basis for future analysis addressing the connection between nervousness and error processing, each quantitatively and conceptually. Specifically, we offer estimates of the impact sizes regarding associations between dimensions of tension and error-monitoring ERPs elicited in commonplace battle duties. This meta-analytic end result offers a extra actual understanding of the earlier literature and might serve to assist researchers design higher research for the longer term with a watch towards statistical energy and precision. We have now additionally articulated a framework that focuses on what enhanced ERN displays about cognitive dysfunction in nervousness. Our view is that enhanced ERN in nervousness indexes the impression of anxious apprehension—i.e., fear—on post-decisional response battle by means of its adverse affect on lively objective upkeep mechanisms and a ensuing compensatory improve in “as-needed” reactive management. Such a dynamic displays what Berggren and Derakshan (2013) name the “hidden price” of tension. As has been urged, beneath easy job circumstances, this compensatory effort permits anxious people to carry out in addition to non-anxious people. Sadly, compensatory results can break down when duties grow to be harder. That’s, enhanced ERN offers an index of how onerous a nervous thoughts has to work to finish even easy duties. It might function a harbinger of wrestle and potential failure on extra advanced duties and presumably real-world adaptation. Certainly, the fixed distraction and compensatory re-focus is illustrative of how nervousness, and fear, particularly, can drain assets and result in practical incapacity.

In sum, we hope this mannequin and our preliminary concepts for future analysis represents only the start of a deeper understanding of what error- and conflict-related ERPs can inform us in regards to the impression of tension on cognition. The promise of extra formalized fashions of cognitive dysfunction in nervousness might be realized to the extent that they provide new insights into how higher to determine and deal with the world’s most ubiquitous psychological well being drawback.

Battle of Curiosity Assertion

The authors declare that the analysis was performed within the absence of any business or monetary relationships that might be construed as a possible battle of curiosity.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Michael Larson for contributing his unpublished ERN information for inclusion within the meta-analysis. The authors would additionally wish to thank Christine Larson for offering the information for the associations between BIS and PSWQ and MASQ-AA. Lastly, the authors wish to thank Greg Hajcak Proudfit, Alexandria Meyer, Gilles Pourtois, and Anna Weinberg for contributing information from their revealed work for inclusion within the meta-analysis.

Footnotes

References

Aarts, Ok., and Pourtois, G. (2012). Nervousness disrupts the evaluative part of efficiency monitoring: an ERP research. Neuropsychologia 50, 1286–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.02.012

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

American Psychiatric Affiliation. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Handbook of Psychological Issues, 4th Edn., Textual content Rev. Washington, DC: Creator.

Amodio, D. M., Grasp, S. L., Yee, C. M., and Taylor, S. E. (2008). Neurocognitive parts of the behavioral inhibition and activation methods: implications for theories of self-regulation. Psychophysiology 45, 11–19.

Bartholow, B. D., Pearson, M. A., Dickter, C. L., Sher, Ok. J., Fabiani, M., and Gratton, G. (2005). Strategic management and medial frontal negativity: past errors and response battle. Psychophysiology 42, 33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00258.x

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Beilock, S. L. (2008). Math efficiency in annoying conditions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 17, 339–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00602.x

Beilock, S. L. (2010). Choke: What the Secrets and techniques of the Mind Reveal About Getting It Proper When You Have To. New York, NY: Free Press, Simon and Schuster.

Beilock, S. L., and Carr, T. H. (2005). When high-powered folks fail: working reminiscence and “choking beneath strain” in math. Psychol. Sci. 16, 101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00789.x

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Berggren, N., and Derakshan, N. (2013). Attentional management deficits in trait nervousness: why you see them and why you do not. Biol. Psychol. 92, 440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.03.007

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Berti, S., Geissler, H.-G., Lachmann, T., and Mecklinger, A. (2000). Occasion-related mind potentials dissociate visible working reminiscence processes beneath categorical and equivalent comparability circumstances. Cogn. Mind Res. 9, 147–155. doi: 10.1016/S0926-6410(99)00051-8

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Beste, C., Konrad, C., Uhlmann, C., Arolt, V., Zwanger, P., and Domschke, Ok. (2013). Neuropeptide S receptor (NPSR1) gene variation modulates response inhibition and error monitoring. Neuroimage 71, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.004

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Boksem, M. A. S., Tops, M., Wester, A. E., Meijman, T. F., and Lorist, M. M. (2006). Error-related ERP parts and particular person variations in punishment and reward sensitivity. Mind Res. 1101, 92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.004

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Borkovec, T. D., and Inz, J. (1990). The character of fear in generalized nervousness dysfunction: a predominance of thought exercise. Behav. Res. Ther. 28, 153–158. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90027-G

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Botvinick, M. M. (2007). Battle monitoring and determination making: reconciling two views on anterior cingulate operate. Cogn. Have an effect on. Behav. Neurosci. 7, 356–366. doi: 10.3758/CABN.7.4.356

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S., and Cohen, J. D. (2001). Battle monitoring and cognitive management. Psychol. Rev. 108, 624–652. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.108.3.624

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Bradley, M. M., Codispoti, M., Cuthbert, B. N., and Lang, P. J. (2001). Emotion and motivation I: defensive and appetitive reactions in image processing. Emotion 1, 276–298. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.276

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Bramon, E., Rabe-Hesketh, S., Sham, P., Murray, R. M., and Frangou, S. (2004). Meta-analysis of the P300 and P50 waveforms in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Res. 70, 315–329. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.004

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Brannick, M. T., Yang, L.-Q., and Cafri, G. (2011). Comparability of weights for meta-analysis of r and d beneath life like circumstances. Org. Res. Strategies 14, 587–607. doi: 10.1177/1094428110368725

Braver, T. S., Grey, J. R., and Burgess, G. C. (2007). “Explaining the various kinds of working reminiscence variation: twin mechanisms of cognitive management,” in Variation in Working Reminiscence, eds A. R. A. Conway, C. Jarrold, M. J. Kane, A. Miyake, and J. N. Towse (New York, NY: Oxford College Press), 76–106.

Braver, T. S., Paxton, J. L., Locke, H. S., and Barch, D. M. (2009). Versatile neural mechanisms of cognitive management inside human prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 7351–7356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808187106

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content

Brown, T. A., and Barlow, D. H. (2009). A proposal for a dimensional classification system based mostly on the shared options of the DSM-IV nervousness and temper problems: implications for evaluation and therapy. Psychol. Assess. 21, 256–271. doi: 10.1037/a0016608

Pubmed Summary | Pubmed Full Textual content | CrossRef Full Textual content